(中文译稿纲要)

(中文译稿纲要)

背景

我们今天的主题是多玛斯主义为什么重要。多玛斯·阿奎那被称为大公教会的天使圣师。他对存在的洞见融会贯通、广泛深邃。多玛斯主义对当代有什么意义呢?今天的讲座会从六个角度对这一问题进行概述。记得多年前一位年轻的牧者对我说:“一件有意思的事情是多少战斗在人心中进行。” 但除了心,有一半在理智中。教会关于人类幸福的许多教导是关乎理智的。智性通过赋予我们终极视野,让我们获得幸福。若能认知真正善好何为,通过热爱该善好,人可以在生命的变数中保持宁静。在今天的世俗时代,大公信仰在公共和媒体领域中极遭反感与厌恶,大公信仰甚至构成了世俗主义的最大挑战。教宗方济各鼓励我们带着自己的信仰现实走进对手的生命中,去转化它。圣多玛斯在实现这一目标方面非常有帮助。

1. 大学的危机

历史上从来没有这么多的人花这么多钱接受大学精英教育,但后者对于他们理解生存意义却帮助不大。大学的危机反映出的是文化危机:当代学术文化缺乏综合一体性,专业分工多元细化,历史实证方法脱离了价值判断,出版物堆积如山。这种针对学生设计出来的类似于超市、缺乏一体性的教育理念,就像专家们提供的专业知识自助餐,看起来五花八门,却没有人告诉你如何将它们整合在一起。四年结束后,你接受的是碎片化、极昂贵、迷失了方向的大学教育。与这种方向迷失形成鲜明对比,圣多玛斯对存在的理解融会贯通、统一大全,并通过不同的知识类层向着终极真理逐步递进。圣多玛斯认为,人对存在现实的认知是一个循序渐进的抽象过程:最初是事物的量化抽象,之后是实物的观察与精准描述,再后是探究事物类型、成因、能力等问题的自然哲学,最后且最高的层级是形而上学,涉及的是存在的真善美等问题。形而上学也是神学出现的地方,天主与存在的第一因联系在了一起。

圣多玛斯展示了不同的智性活动如何渗透现实,并在不同的专业领域中把握事物背后的连续统一。这意味着数学家可以对话哲学家或诗人,哲学家或诗人可以对话神学家,皆因为存在背后的统一真理。哲学家无法取代数学家或科学家,后者也无法取代哲学家。每门学科都有着独立的尊严,也避免了神学的一统独断。如果以信仰的态度从事学术研究,它从自身内整合不同领域的知识、在存在的各个面向中获取真理。如果多玛斯主义的这一特点被捕捉到,智性生活会变得有趣、自由,也会呈现并挑战世俗主义传统的支离破碎的教育观。多玛斯主义是现代大学体系的一种补救。

2. 圣经宗教与现代科学

第二点是现代科学与圣经宗教之间的对立问题。新无神论继承了法国社会学家孔德的预设:现代科学会逐渐取代宗教。古代的孩子们信仰宗教,中世纪的青年学习哲学,现代性的成年人则相信生物学和物理学——这种观点是不可信的。哲学和宗教问题是每个时代人类存在基本的、结构性的部分。如果它们过时,人类也会过时。但现代科学革命仍给天主教神学带来了两个问题:宇宙大爆炸与创世论的问题、进化论和人类起源的问题。圣多玛斯在这里重要的原因有二。一是他区分了主要因果律和次要因果律之间的根本区别。天主赋予一切存在者的存在、是存在自身的给予者。被赋予存在的事物不是被动的,作为自身尊严的一部分,受造物也被赋予了主动的自创能力。天主作为主因与受造物的自发历史过程没有对立。天主赋予了人类理性和自由,同样让宇宙成为一个充满因果律的宇宙,因而科学中发现的因果法则与天主创世之间的对立是荒谬的。二者只是从两种不同、非竞争性的角度考察了同一现实。

二是阿奎那教导人类拥有的灵魂由天主直接创造。身体是灵魂的外在表达,二者是同一实体,这不同于笛卡尔把灵魂与身体分成两个实体。根据教会教导和阿奎那的主张,我们是身体和精神结合的灵性存在。我们通过大脑认知,它是物理性、基础性的认知器官,包含了想象、直觉、记忆、感觉等生物性能力,似乎有证据表明是通过长期进化形成的。

然而,科学永远无法谈论来自非物质性灵魂的哲学问题。从原人到初期人类,他们皆有着复杂的感官记忆、手眼协调、喉音发音等能力,以及抽象思维、 理性判断、自由道德、语言工具、艺术创作。它们不是电子显微镜可以观察到的,且都超越了感官活动,关系着属于精神与灵魂层面的理性理智和自由意志。如果你在阿奎那的学说中理解了这两个原则,即主要因果关系和次要因果关系以及灵魂作为身体的形式,那么你会意识到圣经与现代科学世界观之间没有深刻冲突。

3. 美德真理与人类幸福

我们生活在道德相对主义的时代。大公教会的道德绝对主张可能会被指控为偏执和武断的。对于进步主义者来说,道德观念通常是由其后果、影响决定的。传统的基督教道德教义被视为限制了他人的自由,但它的理由不是出自形而上学或人性层面的论证,而是因为多元主义对人类自由的尊重。这种宽容与包容主义认为只要不伤害他人,每个人都有权利按自己的信念行事。遗憾的是,这种看似宽容的规则不适用于胎儿与重病患者、也不适用于不接受自由主义前提的人群。现代自由主义的这种道德立场是基于对道德共识的绝望,但不是解决价值冲突的方法。

多玛斯与当代人的看法有很大不同。首先,他认为道德或美德的生活主要是出于对幸福与快乐的渴望。但我们获得幸福与快乐的方式取决于如何正确地爱,过美德的生活。爱什么、如何爱决定了一个人的存在结构和幸福根基。快乐是艰难、脆弱的,唯有在天主的爱与善好中才能获得永恒福乐。

基于此,阿奎那认为美德是幸福的基础,因为美德帮助我们获得真正的善好,与天主保持友情。节制的美德让我们平衡地处理与他人、物品的关系;勇气的美德让我们在艰难中坚持不懈;正义的美德使我们正视个体的尊严和权利,公正对待他人是友谊的第一基础;明智的美德让我们在正道行进中有分寸感。阿奎那认为变得明智审慎的方法之一是向审慎的人寻求建议,与对生活和幸福有更深刻认识的人交谈,尤其是牧者。幸福内容之一是如何做明智决定。

我们的幸福同时建立在超德或神学美德的基础上。对天主的信望爱直接来自圣神,后者将超性生命注入灵魂。信德是认知天主;望德是在生活与环境的困境中稳定地、不懈地追求与天主共融;爱德借着恩宠参与到基督的爱中,让我们的心与天主的心走向共融,让我们以基督的爱爱他人。正是来自圣神的超性生命让我们幸福。

4. 圣经作为天主的启示

圣多玛斯教导,我们能够在既非基要主义者又非自由派新教徒的情况下,去相信圣经是真正的历史性的启示。在西方,圣经解释被奇怪的实证主义神学所俘虏,只注意到字面含义,圣经首先被当作技术事实的蓝图。而教父们从未如此看待圣经。另一方面,与之相对,自由派新教徒把圣经当作人类宗教文化的产物,是我们今日开展自由化政治行动的指南。的确,圣经是人类宗教文化的见证,也是人类伦理的泉源之一。但又不仅如此。圣经是受默感的天主圣言。

圣多玛斯直抵根本。对圣多玛斯来说,圣经何为?是为了发现天主是谁。自永恒以来,至圣圣三便定意创造我们,分享给我们祂的三一性格,向我们启示出祂是谁。天主是我们的理智的父亲(God is the Father of our intellect)。他创造了我们,我们能追寻真理,找到祂,进入祂永恒荣福的嗣业之中。人的天职便是领受恩宠,去认知处在完美真福中的天主。这个想法比我们在防卫式的、实证化的基要主义或轻蔑式的、怀疑论的自由主义那里所能找到的,都远为有趣。

根据圣多玛斯,为什么新约会被写下?是为了教导我们,天主降生成人,究竟意味着什么?看到天主的人性面容,会是什么样子?在圣经中,我们有四幅对天主的人性面容的素描:四部福音书。每一部都从一个特定的角度理解基督,然而每一部都引导我们走近同一个人。这一道成肉身的奥秘,正是整部新约的中心。圣多玛斯《神学大全》基督论的第一个问题便是:“为何天主降生成人?” 圣多玛斯认为答案是:我们的原罪。我们随身携带的这些神秘的伤口是什么?为什么自私和非理性的欲望经常困扰着我?恩宠如何帮助我在基督宽仁的光照下生活,找到内在的治愈和力量?多玛斯根据我们戏剧性的人类处境来理解道成肉身。为我们自己的罪所创伤,人需要恩宠、智慧,以及道德和灵性的疗愈。天主成为人,为了“从内部”(from within)修复人的处境,让我们分有基督的恩宠,将我们带回天主。

5. 圣事性的教会

我们生活在一个怪异的诺斯替主义时代,尊奉非肉身化的唯灵主义。人们常常说:“我是属灵的,但我不是宗教的,我不属于任何一个特定的宗教。” 并非如此。人并不仅仅是呆在身体中(inhabit bodies)。人就是身体(are bodies)。而宗教即是:用身体行动来敬拜天主,在身体生活中成为属灵之人。宗教性的内在生活,需要真实化、具体化,需要通过身体显化出来,需要在礼仪祈祷中“肉身化”(incarnated)。所有这些都要求我们归属于一个共同体。启示宗教是天主给人类的情同手足般的纠正。天主给予我们宗教生活的规范形式,以使我们能与天主、与共同体中的他人,共同生活。

圣多玛斯在圣事神学中论及:1. 我们人类,作为理性动物,需要被天主的恩宠所触碰。这就是圣事的实意。通过基督建立的七件圣事,我们领受了至极超越者——天主,领受了对我们的幸福来说最为本质之物——与天主共同生活。就其自身而言,天主的奥秘是纯然超越的,永远逃避我们的把捉;然而在圣事中,我们以最为自然的方式——甚至直接通过感官——领受了这至极超越而又绝对必需者。通过圣经来领受天主,的确非常唯美;可是真正地触碰到天主,只有通过圣事性的生活。想一想婴儿受洗,借由把水倒在他的头上,神性生命被倾注到他无形质的灵魂之中。想一想圣体圣事(Eucharist),你能把基督的身体(一小块面饼)拿在手中,放在舌上;你为基督之死所滋养,你被基督复活的生命所哺育。这些都是如此奥秘,却又如此单纯。

因此,我们通过最为自然、最为适合人的方式领受天主,但是与此同时,2. 这将作为共同体的教会编织成了一体。并非我个人凭借自己的智慧制造出来的教会,而是基督所创立的教会。我们生活在一个宗徒所传、主教神父相继的教会之中。的确,普普通通的主教,普普通通的神父,普普通通的平信徒。普普通通的天主子民,却都依靠圣事这一活生生的纽带而生活,保持为一个家庭,在死而复活的基督之内彼此相连的广大家庭。这是一个严肃的宗教,一个可见的宗教。在其中,你能真正地生活,真正地死亡,真正地获得永恒的生命。人们常常抱怨,天主教太庞大了,太僵化了,但是在我们的人性深处,所有人都渴望皈依的挑战,都呼求成圣的召叫。把一种不严肃的宗教带给其他人,是没有意义的。而圣多玛斯圣事性的视见(sacramental vision)带给我们的便是一个严肃的宗教。圣事是恩宠的肇因。

6. 静观的必要性

我们生活于其中的现代文化,已很难理解静观 (contemplation)了。而圣多玛斯能帮助我们看到,为何静观对我们的幸福来说如此重要。在某种意义上,所有人都或多或少地涉入某些形式的静观。也许我们这里可以判分上下。下等静观依靠视觉技术。关于技术对现代人理智能力的影响,海德格尔有一个有趣的观点:由于现代科学以及与之相伴的技术的进展,人们经由技术所提供的工具来与现实互动,我们的理智便习惯于使用工具来改变世界。但是工具只有在你能理智性地操纵它们时才有用,所以如果你一直是通过自己所主宰的工具来进行思考,那就理智而言,你便成为了特定的人。你将成为一个高效的人,一个运用工具来操纵现实的人。如此,你便进入了单一的效力化的智性环境,而不再能理解馈赠、给予的智性环境,因为这些逃脱了你理智的掌握。

静观始于惊奇,惊奇始于操纵和主宰停止之处。当心灵被吸引入令它心醉神迷之物,真正的问题于焉生起。如果我去操纵一个被给予我的领域,那我将不再充满惊奇,我将不再静观。下等静观的典型代表是X-Box游戏机。游戏、视频与真人秀,所有这些都吸引那些想要延长青春期的心理,但真正在灵性上发生的,在我们内心深处,是逃避主义。我们经常寻求一种逃避,尤其当我们疲惫不堪时——寻求从责任的重担中解脱出来的避难所。我们带着压力回到家中,看电视或玩游戏,以转移我们的焦虑。大脑可以安静地浸入其中,无须再紧张地控制形势,它可以单单随着屏幕的变化而变化。我们的文化正以这种不健康的静观喂养人心。而更深层次的静观来自友谊。在友谊中,我们遭遇比我们更为崇高的现实。每一个人,都有我们所缺乏的某种品质。每一个人,都有独属于他的奥秘尊严。我们永远不能说我们完全了解了某一个人。

广而言之,对多玛斯来说,当我们遭遇善时,便是如此。当我们遭遇存在的奥秘、宇宙,乃至天主时,就更是如此了。我们生活在一个时时邀请我们以惊奇的双目跃然观看的世界之中。进一步地,惊奇邀请我们更深入地探究奥秘,在理解上取得进展。谁会说自己已经完成了对人的思考?谁会说自己已经结束了对存在之奥秘或宇宙之美的思考?谁会说自己已经穷尽了天主的奥秘?随之而来的是神学的静观,静观至圣圣三的奥秘,基督生命的奥秘,圣体圣事的奥秘,教会的奥秘,至福圣母的奥秘。我们的理智最为高贵之处便在于我们为静观而受造。

静观生活,即是对存在那慷慨给予的奥秘的惊奇,以及随之而来的探究这一奥秘的快乐。静观,即是在理智上认识天主是谁,渐渐深入,直至成为天主真正的朋友。传统的道明会神修告诉我们,静观生活向任何一位领受洗礼、领受超性信仰的人开放。如果你有信仰的恩宠,你就可以活出静观的生活。如果你在圣体圣事中与天主与近人彼此交通,你就可以活出静观的生活。如果你念玫瑰经并向至福童贞圣母祈祷,你就可以活出静观的生活。静观,是深入人心创伤的药膏。静观生活给我们的生命奠立秩序,充满我们的心灵,赐给我们平安。

人心唯能安息在至善的怀中。无论人能取得什么成就,永远不能免除他对天主的需要,也永远无法主宰天主的奥秘。人只能通过好学的惊奇,通过静观,通过学习,通过敬拜,通过宗教,来走近天主。圣多玛斯教导我们如何在这个世界上生活,教导我们在天主之光、在朝向天主中来思考这个世界的奥秘。真正的智慧在于,在天主之光中来思考万有,万有都来自祂、借着祂、归于祂。

附语: 内在殿堂

某位东方教父曾谈及“心灵之中的小小圣堂”,心灵的圣堂是我们与天主不断合一、共同生活的地方。但是,我们同样也可以有理智的圣堂,理智的圣堂是我们尝试在天主的光照下来看待世界并向天主表示敬意的地方。在天主之光中来思考现实,使整个世界都进入我们的教会。整个世界都教导我们关于天主的真理。借着真理,在心灵的平安之中,整个世界都将我们带向与天主的和谐共融。如果你有意培育理智的内在殿堂,圣多玛斯将会是很好的伙伴。在这方面,他也是新福传(new evangelization)的导师。因为今天最重要的是,邀请人们在基督教五彩斑斓的美之中,重新发现它的真理,瞻仰基督,“因为在他之内蕴藏着所有智 慧与知识的宝藏”。(老刀 同塵 译)

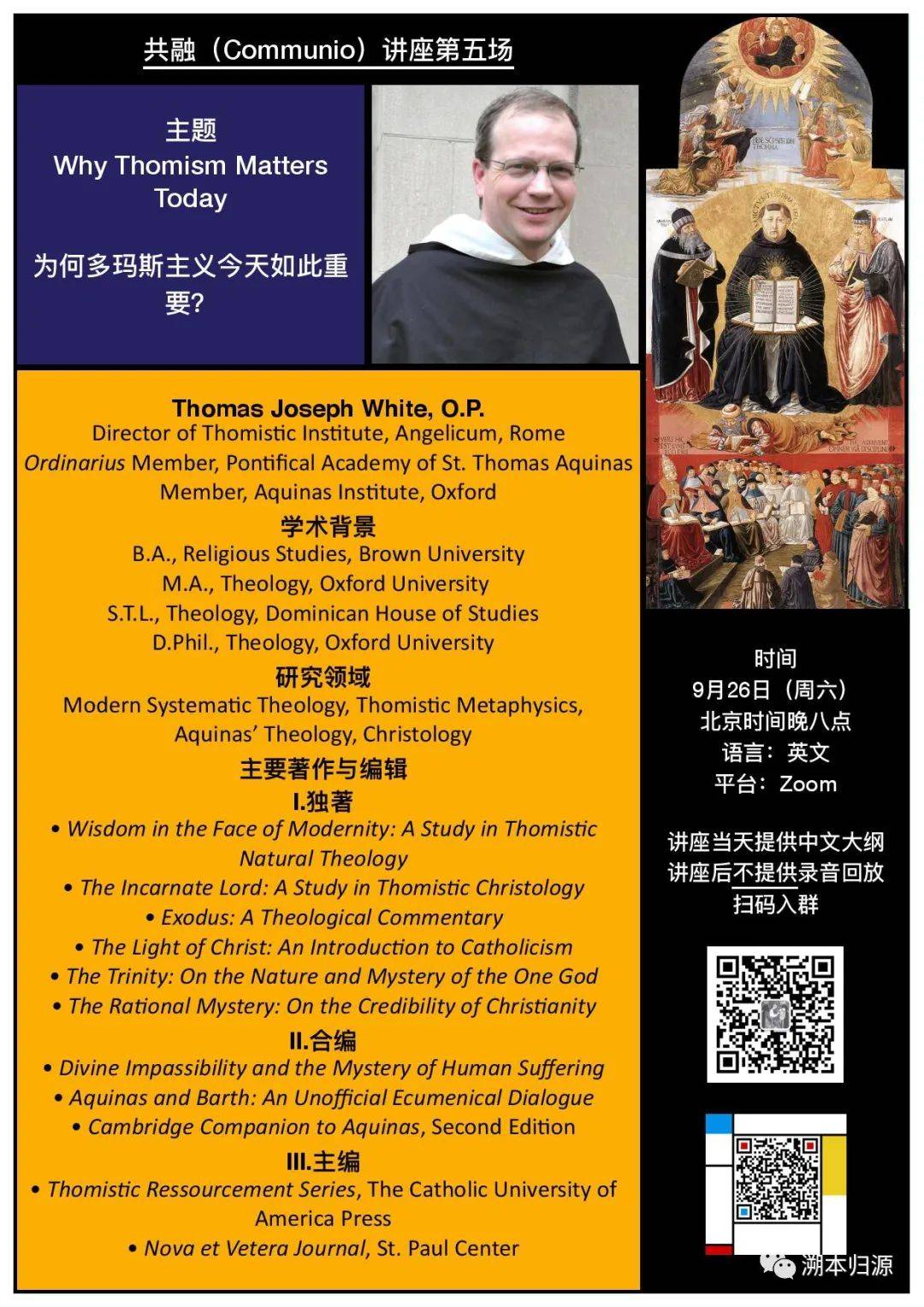

Why Thomism Matters Today

Fr. Thomas Joseph White, O.P.

Thomistic Institute, Angelicum

Our theme is the promise of Thomism. Aquinas is called the doctor communis or common doctor of Catholic theology for a reason. The universality and scope of his insight into reality has a perennial value. The applications of insight can differ, however, in every given age. What is the significance of Thomism in our own era? Why be a Thomist today? The answers presented here serve only as a thumbnail sketch, a little charter regarding the challenges of evangelization—the new evangelization in the Church today, and why St. Thomas’s theology is so vital for this task. I am going to give six brief points as to why Thomism matters.

I remember talking to a young priest many years ago after we had done some evangelization in England for a weekend retreat, and he said to me, “You know it’s funny how much of the battle is in the mind.” What he meant was that we think the struggle for the Catholic faith is primarily in the heart—that conversion is in the heart. Of course, a lot of the battle is in the heart—to discover Christ, to give ourselves to God, to consent, to surrender, to trust, to love, to find peace; but it is also the case that half the battle is in the mind. And that means that actually, a lot of the message of the Church regarding human happiness is about the intellect— intellectual happiness. How does the intellect provide for our deepest happiness? By giving us ultimate perspective. If you know where your true good lies, you can love that good, and in loving that good, you can remain at peace, even in the midst of the storms of life. A lot of the ways in which we navigate life with a deeper, more spiritual joy, and rootedness is through intellectual perspective, gaining the right perspective on things. Truth can be a source of enduring happiness and peace.

We live in an age where there is a profound antipathy to the Catholic faith in the public square and in the media, and for good reason. There is an innate recognition among the advocates of secularism that the Catholic religion is the single most serious adversary to a secular view of the world. They sense that the depth of Catholic teaching regarding human personhood, moral realism, the reality of God, and divine revelation all challenge the status quo at a deep level. Those who take on the Church do so in an attempt to banish one of the most serious enemies to a perennial secularism. Pope Francis helpfully emphasizes the idea of going out to where our adversaries live and challenging them with a different vision of the reality of Christianity than the one that they have in their minds. St. Thomas is very helpful in pursuing this goal—what Pope Benedict called intellectual charity—of finding where the knots are tied in the souls of our contemporaries and trying to untie them and help people find a deeper peace, perspective, serenity, and happiness in the heart and mind through the truth. So I want to give little touchstones here—six touchstones—of where we who are all committed in some way to the evangelization of our culture can think about the truth not as a weapon but as a medicine for the healing of the human mind and heart.

A first point concerns the crisis of the university: Never in the history of the world have so many people spent so much money to study in such elite institutions only to finish with so little plausible understanding of the meaning of their existence. The crisis of the university is really very striking, and it is indicative of a deeper crisis in our culture. What do we see in contemporary academic culture? We see a tendency towards intense personal specialization and away from overarching synthesis, toward empirical and historical study (positivism) and away from value laden judgments that risk incurring the ire of politically correct censors. There is intense publication ambition, in view of tenure and grant bequests. We see a super-market ideal of education as geared toward students’ varied interests, and away from a structured program of integral formation. What ensues is an individualism that obtains on many levels—teacher, student, subject, methodology—that colors the whole education. It’s like a buffet of every expertise on offer from the leading expert, but there’s rarely a mediating discourse or common philosophy that allows you to bring into unity all the various forms of learning. Consider a typical first semester: A class on anthropology; a class on Spanish literature; a class on calculus; a class on biology; and perhaps the philosophy of John Locke. And how is it all united? No one ever tells you. And at the end of four years, did anyone ever seek to tell you? Not usually! So you end up with an education of fragments. And it is extraordinarily expensive! And it leaves you existentially disoriented!

There are some predominant, overarching theories of meaning that are commonplace, either unstated or stated. One is the philosophy of secular political liberalism à la John Rawls; one is a kind of postmodern idea that we can’t really come to any deep unifying discourse about reality; and one is a kind of scientism that thinks that understanding the physical universe through physics, chemistry, and biology is the only true way to access reality. None of these is really full compatible with either of the others, and most people hold intuitively to some kind of unstable mix of the three. In helpful contrast to this disorientation, St. Thomas thinks that we have a differentiated and unified understanding of reality. The mind approaches reality, you might say, at different levels of being. This is a very technical idea. I am going to try to make it simple. It’s called the Degrees of Knowledge, a Thomistic concept made popular by the late 20th century philosopher Jacques Maritain.

St. Thomas thinks that we can selectively look at reality on deeper and deeper speculative levels. An initial level would entail studying quantity alone—abstracting from everything except the quantity of things. He says that that is where you get the science of mathematics and, from a use of mathematics applied to physical beings, the observational sciences. What this gives you is an accurate, predictable description of the quantitatively physical aspect of reality. Then there is the deeper science that looks at natures: philosophy of nature. This is the science where you ask basic philosophical questions about natural kinds (essences), and the causes and the capacities of things. What makes a living thing different from a non-living thing? What is matter? What about time, motion, and change? How do we explain these? Finally, there is a deeper level where you start to study the very existence of things: metaphysics. What does it mean to say that a given reality exists? What are goodness and beauty? Does truth come uniquely from our minds projecting onto reality, or is the state of reality outside our minds the objective measure of the truth of what we think? Ultimately that is where theology comes in. God appears on the horizon of human philosophy as a question about ultimate causes. Why do we live in a world of beings that are all inter-dependent and varied in their qualities and duration of existence? Does there have to be something more? If so, what can we say about God, philosophically speaking?

So there’s this depth perception of reality, and you can look at it at different levels: mathematically, modern scientifically, philosophically, and metaphysically, that is, looking at the very gift of being and starting to think theologically about the giver of being—God.

From this, St. Thomas develops a broader theory about all the different disciplines: math, observational sciences, philosophy, theology, the arts, ethics, politics, and literature. One of the strengths of St. Thomas’s view, which is applicable in a very contemporary way, is that he shows you how different scientific forms of understanding (broadly speaking) help you penetrate reality at different levels. There is particular expertise, but there is also a deeper unity present in our knowledge of things. So, there’s a way that the mathematician should be able to speak to the philosopher or the poet. And there’s a way that the philosopher or the poet should be able to speak to the theologian. And ultimately, truth is one because the intellect is made for being. All that exists—all that is real—can be known even if it is known in different ways.

This may seem like a trivial point, but I think that the Thomistic tradition understands well the unity and integrity of human knowledge and avoids all temptations to theological totalitarianism. By theological totalitarianism, I mean the idea that because one believes in ultimate things about God, he or she should be able to railroad all the lesser disciplines and force them into narrow straitjackets of intellectual presuppositions. St. Thomas notes that even in the natural order, the philosopher can’t replace the mathematician or the observational scientist, but also the converse: the modern scientist cannot replace the philosopher. Each discipline has its own irreducible dignity. The theologian simply can’t replace the philosopher or the mathematician or the scientist. So this religious view of the intellectual life is cosmopolitan and open to all disciplines of learning, but it is also integrated. For Aquinas, all learning is united by a common goal—the pursuit of the truth about reality, considered under various aspects. When people see the intellectual nuance of the Thomist tradition on this point, it becomes intellectually interesting and even liberating. It also becomes more dangerous to secular liberalism, which is increasingly trapped in a factional, fragmented view of education. If you come out of the modern university system, you know this is a problem on some visceral level. Thomism is a remedy.

Christianity and Modern Science

Second point: The perceived opposition between modern science and Biblical religion. Perhaps you have had some exposure to the New Atheism. (It’s crude. We need a better class of atheists.) But if you get into the New Atheism, and look at the blogosphere, what you see is the nineteenth-century presupposition from Auguste Comte, namely that modern science gradually displaces religion. The children of antiquity believe in religion, the adolescents of the middle ages study philosophy, and the grownups of modernity believe in biology and physics. This view of human thought is literally incredible. Philosophical and religious questions are part of the basic structure of human experience in every age, and are never out of date. If they were, then being human itself would somehow become out of date.

However, there are two neuralgic issues that the modern scientific revolution poses for Catholic theology. One concerns Big Bang cosmology and whether the story that cosmologists tell us about the origins of the universe has somehow displaced the Genesis narrative regarding creation ex nihilo. The second is, of course, evolution and the question of the origins of man. St. Thomas is very important here for two reasons.

First: St. Thomas’s fundamental distinction between primary causality and secondary causality. What does God give to creation? He gives it existence and being, so that anything we discover in the world scientifically is something that exists. If it’s real, if we’ve discovered it to be real, it has being. And if it has being, it has a giver of being. God’s giving things being doesn’t entail making then merely passive; rather, part of the dignity of creatures is that they are created in such a way as to be themselves true causes. This is the case both in the physical order and in the spiritual order. There is not an opposition between God causing something natural to exist, and that created reality having its own history and development as a true, physical cause. And there is not an opposition between God causing something personal to exist, and that reality having its own history and development as a free spiritual cause. God has caused human beings to be and has given us a nature that is rational and free. So we’re free because God actively causes us to be creatures who are free. But likewise with the whole physical universe: God has caused the universe to be a universe of causes. So the idea that you can have a confrontation between what you discover in the domain of causality through the sciences and what God has given in creation is an absurdity. There’s no conflict, because everything that you discover in the world, in the web of physical, chemical, and biological causes, is what God has given being and so has given to be causes of other things in the created order. Understood this way, there is no opposition between the doctrine of creation ex nihilo and modern Big-Bang cosmology. They examine the same reality from two different, non-competitive perspectives.

Second: Aquinas teaches that the human person has a spiritual soul created directly by God, but that the soul is the form of the body, so that we are one substance. This can be contrasted with the teaching of René Descartes, who affirms that the spiritual soul is a distinct substance from the body, as if you and I were two things, a spirit who is accidentally connected to a machine. (Descartes improbably affirms that the two are connected at the pineal gland.) As the Catholic Church has taught and as Aquinas argues philosophically, we are just one being— body and soul—a spiritual animal in which the spiritual soul informs the body. But this idea has repercussions for our theory of noetics (how we know things). We know all the realities we encounter (including ourselves) through the medium our senses. We therefore also know things through our brain, which serves as a physical organ underlying sense experiences. We know about objects in part through our sense memory, suggesting brain patterns for recognition and imagination. In short, we know stuff as animals know stuff. Think of how you throw a ball and the dog knows where the ball went. He finds a way through the fence, finds the ball and brings it back, remembering how to play the game. Sense data and memory are at work, grounded in the physical organ of the brain. We often work that way too, remembering where we put the coffee cup, or something else—like the keys to the car. So we work a lot through animal instincts, memory, and senses, and that animal capacity in us could have developed through a long evolutionary process. There seems to be excellent evidence that it did.

Here’s the important point, however: what science by its very nature can never talk about competently is the philosophical question of the immaterial soul. There was a passage from very developed hominids to the first human beings. This is the passage from hominids having very sophisticated sense memory and hand-eye coordination, or guttural sound capacities, to the formulation of abstract concepts, reasonable deliberation, human freedom, intelligible language, and the human arts. And that passage is not one that you can find under an electron microscope, because what’s new when you encounter rational human nature per se is the spiritual soul, which entails more than sensation. It also entails rational intellect and voluntary free-will. And that means conceptuality and universal denotations in language, that means free action and moral responsibility, that means religion and ritual, that means games and arts, that means marriage. It means a whole lot of things that are specifically human. And you’re not going to be able to see it through the medium of the modern sciences. You can infer it somewhat paleontologically, because you can see that the physical culture of homo sapiens started humanizing progressively; you can see cave art and the use of language and complex tools.

If you start to get these two principles right in Aquinas—primary causality and secondary causality and the soul as form of the body, but as a new presence of something in a rational animal—that’s the beginning of unknotting all the false oppositions between the Bible and modern science. And with those two tools from St. Thomas, with some work, you can actually show that there are no profound conflicts between Scripture and the modern scientific worldview.

Moral Truth Claims and Human Happiness

Third point: We live in an age in which absolute moral truth claims are perceived as arbitrary moralism. Posit some important Catholic moral truth claim around the water cooler at work; it’s not going to be easy. You may be accused of bigotry, or at least arbitrary, subjective moralism. Sometimes it’s necessary to go through those steps in order to say to our skeptical contemporaries, “well you know, I think that’s not true, and here’s why.” After all, a Christian is called upon give reasons for his or her belief, and to have evangelical courage. But we definitely live in a time in which moral truth claims are perceived as largely arbitrary impositions. Our current predicament originates in many ways from the cultural ethos of modern liberalism. For progressivist liberals, moral truth claims typically are evaluated in terms of their political effects. Will they be inclusive or exclusive? Traditional Christian moral teachings, especially in the domains of sexuality and human life, are perceived as limitations placed on the freedom of others, arbitrarily and without justification. This dismissal of the Christian tradition is usually not based on appeal to any grand metaphysical theory of human nature, but on the concern to respect human freedom in a pluralistic society. The governing principle of political life is tolerance for the sake of greater inclusion. From this a strategy emerges: if you feel sincerely about it, you should be able to act on what you believe in. If another feels differently, he or she should be able to act differently. The important thing is that everyone can do what he or she believes in as long as nobody hurts anybody else. As we know, however, this seemingly tolerant rule does not apply to the unborn or the very ill who might be subject to euthanasia, nor do equal rights always extend to those who question the basic philosophical premises of liberal progressivism. Away with the intolerant! At heart, this moral stance of modern liberalism is based on a deep down despair, despair of moral consensus, and we live in an age with profound moral non-consensus. But this isn’t the only way to approach questions of morality!

I want to explain briefly how Thomistic moral theology is a lot like learning to play jazz. This is a view that differs significantly from what our contemporaries think, but which is in fact very realistic. What do I mean by that? Well, first of all, St. Thomas thinks the moral life is primarily about the desire for happiness. The reason you try to act some ways and not other ways is to flourish as a human being—to be a happy human being. And the way we become happy is by love; it’s by loving rightly and well and by living virtuously that we become happy. The question then becomes, what do you love? “Tell me where you dwell, and I will tell you what you are. Tell me what you love, and I will tell you what you will become.” So it’s what you love and how you love rightly and well or poorly and viciously that determines the shape of your character. For Aquinas, this is where the burden of human existence is grounded. It’s the burden of trying to become a person of happiness. And for St. Thomas, this is perceived to be hard. Being really happy is difficult. It’s a life-long journey. And it’s precarious. It’s actually fragile. He thinks happiness in this world is fragile and best achieved when we have a deeply rooted happiness in the love of God because God is unchanging, brilliantly good, and always interesting. God is always there, and God is eternal.

From this idea that we’re made for happiness, Aquinas develops the theme of the stabilization of our good desires for happiness through virtue. The virtues are stable dispositions we can acquire over time that strengthen us in our pursuit of what is genuinely good. They allow us to act consistently in a poised, balanced way, so as to live in stable friendship with God and other human persons. You have heard of the cardinal virtues, no? I mean the virtues of temperance: the balanced use of sense goods in view of personal relationships that are spiritual and self-giving; fortitude: to endure and persevere with character through difficult situations; justice: to acknowledge the human dignity and rights of others in a due way. To treat other people with justice is the first basis of friendship. Aquinas says if you want to be friends with people then to treat them justly and be affable. Affability is a kind of justice by showing other people kindness and recognizing their goodness. It’s not yet friendship; it’s the beginning of friendship. And, finally, prudence: knowing intellectually how to live rightly and well. Should I take this job or that, date this person or not, apologize or instead insist on the truth of my viewpoint (or both)? What actions lead to greater love and personal growth and what actions diminish us or others? This is a basic question of prudence. Aquinas thinks part of the way you become prudent is to ask people who are prudent for advice. To talk to people who have some deeper understanding about how to live, and how to be happy. This is a thing one sees frequently as a priest. People frequently come to speak to priests to ask advice about important decisions in life. (So it is important for the priest himself to seek to become a prudent person!) The deeper point here, however, is that one of the main things that people are looking for when they’re looking for happiness is how to make wise decisions.

In addition and in fact most fundamentally, our happiness depends on the theological virtues: faith in God, hope in God, and charity towards God and neighbor. These are the virtues that are given to us directly by the Holy Spirit, infusing supernatural life into the soul. Faith is the stable disposition given to the mind to know God, to discover God in Christ and to grow in understanding Christ and his commandments. Hope is the stable disposition to tend toward union with God, even in the midst of all life-circumstances and difficulties, and to persevere in seeking God amidst all things. Charity is the grace of participation in the love of Christ himself. Charity unites our hearts mystically with the heart of God, and moves us to love others in light of Christ’s own love for them. And it’s the development of this higher, supernatural life in the spirit that makes us especially happy.

However, as each of us knows, the path toward virtue is fraught with difficulties. In the course of life, you encounter difficult situations. For example, my mother and my sister aren’t talking. They’re going to be there at Thanksgiving. If I go home for Thanksgiving, and I have to deal with my mother and my sister, I might have a breakdown where I have to tell my sister all the reasons I think she’s really treated my mother badly. I don’t know if I have the virtue to do this. I might be a coward or a tyrant. The very thought of the conversation makes me want to avoid the occasion. But then I would hurt my entire family. So should I go home or not? These are prudential decisions. Sometimes the brave thing to do is flee. Sometimes the brave thing to do is engage and ask for the grace to endure, to be patient and charitable.

And this is where it becomes like jazz. A great jazz musician has to know the canon of ordinary music. These five players who get in a room, even if they’ve rehearsed (but often they haven’t rehearsed), start playing in one key; and they start moving down a key, and then they move up three keys, and then they start innovating. They are listening to each other. And then they’re moving together with this improvising jazz at a very high level; this requires a lot of refinement, mechanics, and knowledge of the art of playing in a more canonical, predictable way. Because they’ve mastered that basic level, when they get to hard cases of innovation, they can move with the flow of music, and that’s what the moral thinking of Aquinas is about. It’s about trying to acquire the virtues and prudence to a sufficient degree, so that when you’re in these delicate situations, you can actually preserve love in all things, you can stay in the stream of music—preserving moral harmony—as situations move in a sort of jerky, unpredictable fashion, to remain in charity and in prudence. Moral theology for Aquinas is about getting into that stream of knowledge and love and staying there. And staying in the rhythm of the Holy Spirit. It’s a very attractive vision. The point is that there is a kind of depth there that is just not the hollow moralism that people take us to be advocating.

The Bible as Divine Revelation

Fourth point: St. Thomas teaches us how to believe that the Bible is authentic historical revelation without becoming either a fundamentalist or a liberal Protestant. The big problem in our culture with the Bible, especially in the United States, is that in some ways the Bible has been taken captive by a kind of nineteenth-century Protestant positivism that is literalistic. How many soldiers in David’s army died that day? Are the six days of the first Genesis creation narrative historical or symbolic? (Hint: the sun is created on the fourth day.) It is not fair to say of contemporary Evangelicals that these are their main priorities in interpreting Scripture, but nineteenth-century theories of inspiration have indeed gotten into the water and have become very prevalent, making arguments about literalism the most frequent disputes in people’s treatment of the Bible. The New Atheists frequently ridicule, for example, a very naïve reading of the literal sense of Scripture, a naiveté that they paradoxically share with the fundamentalists they take issue with. (Otherwise they would not be dismissing the Scriptures so readily!) And of course when you get into the six days of creation, which are clearly symbolic, or the question of Methuselah living 900 years, the Bible is simply taken captive by strange positivist theologies that treat it above all as a blueprint of technical facts. Which, by the way, is what none of the Fathers of the Church thought about the Bible. And then you get the counter-reaction, which is the liberal Protestant view that the Bible is above all a product of the religious culture of human beings, and that it serves for us today as an inspiration (lower case “i”) for prophetic (lower case “p”) Liberal (“upper case L”) political action. Well, of course, the Bible is a testimony to the religious culture of human beings, and it is a resource for human ethics. But not just that. It is also the inspired Word of God.

St. Thomas goes to the essential. What is the Bible about for St. Thomas? Finding out who God is. The Holy Trinity wanted from all eternity to create us so that God could share with us his Trinitarian identity, revealing to us who He is. God is the Father of our intellect. He made us so that we could seek the truth, find Him, and enter into the inheritance of His eternal happiness. The vocation of the human person is to receive grace, and the knowledge of who God is in his own perfect beatitude. That’s a much more interesting idea than what we find in the defensive positivism of fundamentalism, or in the dismissive skepticism of liberalism.

Why is the New Testament written, according to St. Thomas? To teach us what it means that God became a human being. What would it be like to see the human face of God? You have four portraits in the Bible of the human face of God: the four canonical Gospels. Each considers Christ from a different angle, but each also allows you to approach the same person. At the heart of the New Testament is this mystery of the Incarnation. The first question St. Thomas asks in his treatise on Christ is “Why did God become a human being?” That’s an interesting Biblical question. Aquinas responds by considering the consequences of original sin. What is this mysterious network of wounds I’m carrying around in myself? Why do selfishness and irrational desire plague me as a person? How does grace help me to live in the light of the mercy of Christ, and to find inner healing and strength? Aquinas understands the Incarnation against the backdrop of our dramatic human situation. Wounded by our own sins, the human race stands in need of grace, of wisdom, of moral and spiritual healing. God became human in order to restore our human condition “from within” and to lead us back to God, by participation in the grace of Christ. Aquinas has a very deep reading of the Bible, and his beautiful interpretation of the life of Christ in the Summa Theologiae is accessible to anyone who takes a little time to read it. Following Aquinas on this and other points of biblical theology gives us an understanding of the Scriptures that is simultaneously very traditional and very measured.

Fifth point: The sacramental Church. We live in an age of strange Gnostic, a-corporeal spiritualism. What does it to mean to say that you are spiritual, but not religious? It must mean something, but it cannot be good. Why? Because as human beings we don’t just inhabit bodies. We also are bodies, and religion is about being spiritual in your bodily life by worshipping God through physical actions. The traditional list of religious practices includes devotion (which is in the heart), prayer (which is in the mind), physical gestures of adoration, sacrifices, oaths, tithes, and vows. The internal life of religion, to be real and concrete, needs to move outward through the body, and to be “incarnated” in the context of liturgical prayer. All of this entails belonging to community and being committed to regular actions of liturgical prayer in that community. So religion is something you live out as an animal, a rational animal that is radically religious and made for God.

We talk in religious life about fraternal correction. This is when one member of a religious order attempts with charity and truthfulness to make clear to another the need for moral conversion on some matter. Typically the most difficult part is being able to hear the correction when a brother comes to talk to you about a thing you need to change. And it’s a mercy if it is said well. Revealed religion is God’s fraternal correction to humanity. God is giving us normative forms of religious life by which we can live together with God and others in a community.

In his sacramental theology, Aquinas, makes two great points that are very pertinent in this regard. One is that we are, as animals, in need of being touched by the grace of God. This is the point of the sacraments. In the seven sacraments instituted by Christ, we are receiving what is most transcendent and what is most essential to our happiness: God and life with God. In itself, the mystery of God is transcendent and evades us, but in the sacraments we receive what is most transcendent—what we most need—in the most connatural way, even directly through the senses. Not even through a book! That’s a very beautiful way to receive God (through the Scriptures), but really to touch God, that’s the sacramental life. It’s very interesting to watch a baby being baptized and to think about how Divine Life is being infused into the immaterial soul of this child by pouring water on its head. Or the Eucharist: you can hold it in your hand, you can receive it on your tongue. You are being nourished by the death of Christ; you are being nourished by the life of Christ resurrected. That is very mysterious, but it is so simple. It’s about receiving love from God in the most connatural way and then, when we receive these physical signs, grace truly acts upon us! When someone says the words of pardon over you in the sacrament of confession—when they say little words over you—Christ acts and your sins are forgiven. It’s amazing!

So we receive God through the most connatural forms but also secondly, this knits together the Church as a community, not a church of my own making in my own mind, but the Church that Christ founded. We live in the Church that the Apostles founded, based on the apostolic succession of the bishops and priests. Yes, the mediocre bishops and priests and the mediocre lay people. The mediocre people of God, but kept alive through this living bond of the sacraments that keeps us as a family bound together in the death and resurrection of Christ. This is a serious religion, a visible religion. One in which you can truly live, truly die, and truly attain to eternal life. Human beings put up protests and say that Catholicism is too monolithic, but deep down our human nature is made for the kinds of challenge to conversion and holiness that traditional Catholicism presents. There is no point in proposing to other people an unserious religion. And Aquinas’ sacramental vision gives you a serious religion to propose to people. The sacraments are causes of grace. God causes grace in the soul through this set of physical gestures that Christ gave the Apostles, that the Apostles gave to the Church, and that the Church brings to us.

The Necessity of Contemplation

Sixth and final point. We live in a culture that has a very difficult time understanding contemplation. And St. Thomas helps us see why contemplation is so important to our happiness. In a certain sense everyone engages in some form of contemplation. Here we might distinguish what is low-grade from what is high-grade. Low-grade contemplation in our culture is typically dependent on visual technology. Martin Heidegger has an interesting point about the influence of technology on the modern intellect. His claim is this: because of the development of modern sciences and the technology that accompanies it, a lot of us interact with reality administratively through the tools that technology places at our service. Our intellects get used to using tools that allow us to transform the world. But the thing about tools is that they can only be useful if you can master them intellectually. So you become a certain kind of person intellectually if all you ever think about is the medium in which you dominate. What you become is a person of efficiency, a person who uses tools well in order to master reality and order it, as an efficient person. That’s good, but then you enter the intellectual environment of efficiency, and you lose the intellectual environment of gratuity, of something that is given, that’s outside your intellectual sufficiency and command. However, contemplation begins with wonder, where mastery and domination cease, when the mind is drawn into what fascinates it, what raises real questions. If I can master a given domain, then I no longer am filled with wonder, and I’m not contemplating.

A simple, but very elevated example of contemplation is pictorial art. If you go to museums, people are typically standing or sitting there staring at pictures. Just gazing and looking. Actually, philosophically speaking, it is not so easy to say what they are doing! Now maybe they are just trying to look pretentious and intelligent. But it is interesting because other animals don’t do this. Is this due to being a rational animal? Human beings alone produce pictorial art and human beings alone gaze at it, and study it. We contemplate it. In seeing a Rembrandt, we can rightly think, “that’s very profound; That’s interesting; what’s going on there?” The museum tour guide, if he or she is good, tries to help you contemplate it more profoundly. Sometimes it requires more thinking; sometimes it is just seeing the pictorial beauty; and sometimes, it is seeing the spiritual beauty that the artist is trying to depict. That’s just an example—it’s an elevated example.

I think the low-grade version of contemplation is X-box. The video game, the YouTube video, the reality television show. All of these appeal to a psychology of prolonged adolescence, but what it really is going on in us spiritually, deep down is escapism. We are often looking for an escape, especially when we are tired—seeking a refuge from the burdens of responsibility. People come home stressed, and they watch hours of television or play video games because it displaces their worries. The mind can immerse itself restfully in something where it no longer has to stressfully master the situation. It can just go with the flow of looking at the screen. This is the diet of unhealthy contemplation with which our culture is feeding the human mind.

But the deeper forms of contemplation happen through friendship. In friendship you’re in front of a reality superior to you. Another human being, every human being, has some qualities that I don’t have. And it’s true of you or me with regard to every other human being. There is a mysterious dignity that is distinctive to every human being. No matter how much you think you understand a human person, if you begin to think you have knowledge of him that is total and fully comprehensive, you’re in error. This is the problem with ideologies that try to explain the human person or indoctrinate along a scientistic, Marxist, or Freudian line of thinking. The human being is always more than a particular intellectual ideology can ever understand.

For Aquinas you begin to contemplate when you encounter a good that your intellect has to ponder, which it can’t fully comprehend. This, of course, is all the more true when it comes to the major metaphysical questions, with the whole mystery of existence, and the cosmos, and with God. We live in a universe that actually invites us to a sense of studious wonder. Not just wonder in the form of resignation: “Oh, who can really say, it’s all so mysterious, I’m going to go back to my coffee and my reality TV show.” No! We live in a universe that invites studious wonder. It’s a wonder which invites us to study the mystery more deeply and to make progress in understanding. Who will ever say that they have finished thinking about what a human person is? Who will every say that they have finished thinking about the mystery of existence, or the universe’s beauty? Who will ever say that they have finished thinking about the mystery of God? And then there is theological contemplation, which contemplates the mystery of the Holy Trinity, the mysteries of life of Christ, the mystery of the Eucharist, the mystery of the Church, the mystery of the Blessed Mother. The highest nobility of our intellect is that we are made for contemplation. That doesn’t provide a salary. Nobody is going to pay you for that, really. People may give donations to contemplative nuns, no doubt because they sense that the contemplative life recalls us to the essential things in life. But, at its heart the contemplative life is about wonder at the gratuitous mystery of being and the delight of studying that mystery. Contemplation is about making progress intellectually in understanding who God is, so as to become true friends with God.

And the contemplative life, traditional Dominican spirituality teaches us, is available to every human being by virtue of supernatural faith, which you received at baptism. If you have the grace of faith, you can live the contemplative life. If you commune in the Eucharist, you can live the contemplative life. If you have the rosary and pray to the Blessed Virgin Mary, you can live the contemplative life. And this is the deepest salve placed on the wound of the human heart. The contemplative life gives order to our lives, fulfills our hearts and gives us peace.

I’m going to finish now with happiness. The human heart is only at peace and rest when it finds an ultimate good that it can posses with stability and joy. Really in the end—as much as that can be friendship, it can be marriage and children, it can be meaningful work, it can be the love of the search for the Truth, natural and supernatural—the ultimate rest of the human heart is in God. No matter what the achievements of the human race, it is never going to be free of its need for God, nor be able to dominate the mystery of God. You can only approach him through a studious wonder, through contemplation, through learning, through devotion, through religion. St. Thomas gives us clues for how to live in this world while thinking about the mystery of this world in light of God, unto God. That’s what he calls wisdom: to think about all things in the light of God, and for God, and as returning to God. To be on a pilgrimage in this world, headed back toward God, intellectually trying to think about things in light of God, and trying to find joy through contemplating God in faith. This heals the heart because it gives the heart a place of rest. Contemplation is something very powerful. Eucharistic adoration is one of the ordinary forms of contemplation at work in the Church that converts people all the time. It is such a profound contemplative encounter with the presence of Christ! St. Thomas helps us become people who have the habit of contemplation, who habitually seek to find God in silent prayer.

There was an Eastern Father who talked about developing what he called “a little chapel of the heart.” Not like the chapels we visit that are so beautiful, or the large churches we pray in, but the chapel that we carry about with us, the chapel St. Catherine of Siena called the interior cell. The chapel of our heart is where we live in continual unity with God. But, you can also talk about a little chapel of the mind. The mind is a place where we are trying to see the world in light of God, and give homage to God, and therefore live continually in the happiness provided by authentic wisdom. Thinking about reality in the light of God makes the whole world into our church. The whole world is teaching us the truths about God. The whole world is bringing us into harmony and communion with God in peace of heart through the Truth. St. Thomas is an excellent companion to have as you cultivate this interior chapel of the mind. In this way he is also a mentor in the new evangelization. For what is essential today is to invite human beings to discover anew the truth of Christianity in all its variegated beauty, and to gaze upon Christ, “in whom are hidden all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge” (Col. 2:3).(同塵 老刀 整理)

(中文译稿纲要)

(中文译稿纲要)