[1] 见作者简介

[2] Avery Robert Dulles, Models of Revelation (New York: Doubleday Books, 1983), 3-17.

[3] 下文中用“信仰”和“信心”对应英文中Faith的含义,Belief则翻译为信念。

[4] Gotthold Lessing, Philosophical and Theological Writings, translated by H. B. Nisbet (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 83-88.

[5] Lessing, Philosophical and Theological Writings, 61-80.

[6] Alvin Plantinga, Warranted Christian Belief (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 80-81。 下文简写为WCB。

[7] Nicholas Wolterstorff, Reason Within the Bounds of Religion (Second Edition), (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999), 28。也参见 WCB, 84. 在认知结构上,基础主义主张存在一个命题或多个命题能够成为其他命题的基础,这些被称之为基本命题,它们构成了人的知识结构的基础。只有当一个命题是不证自明,或不可更改(incorrigible),或对人而言在知觉上是明确时,这个命题才能够成为合适的基础命题。

[8] 也称为圣经历史鉴别学或者高等批判,下文中统一简写为历史批判。在18世纪的德国,由旧约学者艾希霍恩(J.G.Eichhorn ,1752-1827), 盖博乐(J.P. Gabler , 1753-1826), 维特(W.M.L. de Wette, 1780-1849) 等以及新约学者 和后黑格尔学派的学者,赫尔德(Johann Gottfried Herder,1744-1803),斯特劳斯(D.F.Strauss, 1808-1874)等发展出了的学科,主要关注文本的形成,历史的耶稣等一系列的问题,可参见, James C. Livingston, Modern Christian Thought Vol. 1 : The Enlightenment and The Nineteenth Century (Second Edition), (Minneapolis: Fortress Press), 237-50.

[9] Claude Welch, Protestant Thought in the Nineteenth Century Vol.2, 1870-1914 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1985), 1-99; 146-182; 266-301. 克劳德(Claude) 介绍了利切尔(Ritschl)学派之后圣经批判的发展情况,特别在第八章关于特洛尔奇(Troeltsch)的讨论中,重点讨论了关于历史上的耶稣、历史意识和圣经批判的发展。关于这段时期圣经解释学的发展,见Werner Jeanrond, Theological Hermeneutics: Development and Significance (London: SCM Press, 1994), 122-26.

[10] WCB, 388.

[11] Jeanrond, Theological Hermeneutics,126.

[12] Karl Barth, A Unique Time of God: Karl Barth’s WWI Sermons, translated and edited by William Klempa (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2016), 21-30. Eberhard Busch, Karl Barth: His Life from Letters and Autobiographical Texts (Eugene, Or: Wipf and Stock, 2005) 60-198; Simon Fisher, Revelatory Positivism? Barth’s Earliest Theology and the Marburg School (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988) 本书介绍了巴特和赫曼(Herrmann)以及新康德主义的关系. James M. Robinson ed. , The Beginnings of Dialectical Theology (Richmond: John Knox Press, 1968) 59-161.

[13] 特洛尔奇对古格庭(Gogarten)的批判性回应, “An Apple from the Tree of Kierkegaard,”见The Beginnings of Dialectical Theology,312-27. 以及Van Austin Harvey, The Historian and The Believer: The Morality of Historical Knowledge and Christian Belief (New York: Macmillan, 1966),3-35.

[14] Karl Barth, The Epistle to the Romans (Sixth Edition), translated by Edwyn C. Hoskyns (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1968), 1.

[15] Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, Vol. I/1, Edited by G.W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance (Edinburgh: T&T. Clark, 2010 ),284-85. (以下简写为CD)。

[16] CD, I/1, 320.

[17] CD, I/1, 320.

[18] CD, I/1, 307-08.

[19] Barth, The Word of God and Theology, 79-80.

[20] 在巴特的神学观点变化中,存在两种观点,认为巴特在这段时期思想上出现了关键的变化如巴尔萨撒(Hans Urs von Balthasar), 而麦科马克(Bruce MaCormack)等则不同意这种观点,本文的一个前提假设是,巴特的圣经观在《罗马书注释》后尽管有修正,但是始终具有立场的连续性和一致性。参见,Hans Urs von Balthasar, The Theology of Karl Barth (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1951), 以及Bruce L. McCormack, Karl Barth’s Critically Realistic Dialectical Theology: Its Genesis and Development 1909-1936 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 412-39.

[21] Karl Barth, Anselm: Fides Quaerens Intellectum: Anselm’s Proof of the Existence of God in the Context of his Theological Scheme (Richmond: John Knox Press, 1960), 40-42.

[22] CD, I/2, 457-72.

[23] CD, I/2, 673-681.

[24] CD, I/2, 700.

[25] Barth, The Epistle to the Romans, 10.

[26] Barth, The Epistle to the Romans, 8.

[27] Barth, The Epistle to the Romans, 8.

[28] Karl Barth, The Word of God and Theology, translated by A. Marga (London; New York: T&T Clark), 184-196.

[29] CD, I/2, 712-13.

[30] Robert W. Jenson, Systematic Theology Vol.1 (Oxford: Oxford University Press,1997), 21.

[31] CD, I/2, 717-20

[32] CD, I/2, 720.

[33] CD, I/2, 726-27.

[34] Bruce McCormack, “Historical Criticism and Dogmatic Interest in Karl Barth’s Theological Exegesis of the New Testament,”收录在Biblical Hermeneutics in Historical Perspective (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1991), 331-32.

[35] CD, I/1, 40.

[36] CD, I/2, 737-39.

[37] Jeanrond, Theological Hermeneutics, 134.

[38] Wolfhart Pannenberg, Systematic Theology Vol.1,Translated by Geoffrey W. Bromiley (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing, 1991), 194-95. Adolf J Jülicher, “A Modern Interpreter of Paul,” 收录在The Beginnings of Dialectical Theology, 72-81. 句利齐(Jülicher)批评巴特是用现在的世界观理解圣经时代特别是保罗时代的世界观是一种不科学的解释学。在沃莱斯(Wallace )则认为巴特这种祛历史性的解释方法和当代解释学具有某种亲缘性,也就是关注文本本身的文法结构而忽视理解作者的意图,见Mark I.Wallace, “Karl Barth’s Hermeneutic: A Way Beyond the Impasse.” The Journal of Religion 68, no. 3 (1988): 396-410.其他对巴特圣经解释方法的总结和批评也可以见,Richard E. Burnett, Karl Barth’s Theological Exegesis: The Hermeneutical Principles of the Romerbrief Period. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing, 2004), 255-260.

[39] Jeanrond, Theological Hermeneutics,136; David H. Kelsey, The Uses of Scripture in Recent Theology (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1975),49-50.

[40] Harvey, The Historian and The Believer, 158-59。吉尔克(Gilkey)也批评认为巴特和其他新正统的这种解释立场实际上没有考虑到古代世界和现代世界之间人们的宇宙论和本体论的理解是完全不同的,而巴特等新正统主义者是直接将自己理解的宇宙论和本体论来理解古代的世界。并且他主张对于当代的人和圣经中的宇宙观所理解的世界已经完全不同,尽管对于圣经中的人相信神迹,但是对于现代世界的人必须用科学、理性的因果观念来对此进行解释。Langdon B. Gilkey, “Cosmology, ontology, and the travail of biblical language.” The Journal of Religion 41, no. 3 (1961): 194-205.

[41] Bruce L. McCormack, Orthodox and Modern: Studies in the Theology of Karl Barth (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008), 35-39. McCormack认为巴特的立场是超基础主义(transfoundationalism).

[42] McCormack, “Historical Criticism and Dogmatic Interest in Karl Barth’s Theological Exegesis of the New Testament,” 337-38.

[43] 本文主要聚焦在普兰丁格和沃特斯多夫的观点上,原因在于很大程度上他们具有共同的立场和观点。

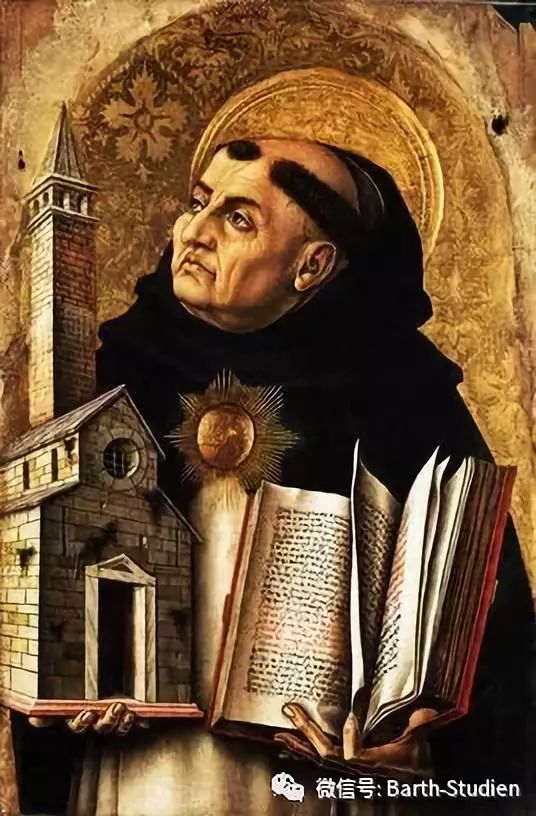

[44] 归正宗认识论学者 对巴特圣经解释学的讨论,可以见Nicholas Wolterstorff, Divine Discourse: Philosophical Reflections on the Claim that God Speaks (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 63-74. 与巴特不同的是,沃特斯多夫对于上帝的行动和上帝的道之间作出了区分。普兰丁格多次指出他提出的模型中概括了奥古斯丁、阿奎纳、加尔文和巴特共享的基督教信念, 见WCB, 245,374.

[45] 在最近的研究中,狄勒(Kevin Diller)将巴特和普兰丁格的认识论进行了比较研究,他也认为巴特和普兰丁格的认识论可以进行互补,但是在比较巴特和普兰丁格对于圣经论的观点时,Diller忽视了这两者的共同点是在回应历史批判的解释方法,相反,狄勒仅仅关注到了两者的圣经本体论上,认为通过将两者观点的结合,来确保圣经本身作为上帝启示的可信。在讨论圣经解释过程中,狄勒仅关注了圣灵在解释过程中的作用,遗憾地他几乎没有讨论巴特神学解释中重要的认识论的主体问题,也没有关注到归正宗认识论对于历史批判的批评。见Kevin Diller, Theology’s Epistemological Dilemma: How Karl Barth and Alvin Plantinga Provide a Unified Response ( Intervarsity Press, 2014), 170-94.

[46] James C. Livingston, Francis Schüssler Fiorenza, with Sarah Coakley and James H. Evans. Jr., Modern Christian Thought: the Twentieth Century (Second Edition), (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2006),506-07.

[47]确保这个词在归正宗认识论具有特别的定义:对于一个信念,当且仅当它是由合适运作的认知功能所产生,并且该认知功能没有发生失序或紊乱时,被称为确保的信念,并且该信念具有了成为知识的条件(见WCB, 153-54)。

[48] Wolterstorff, Reason Within the Bounds of Religion, 50-53.在这里,沃特斯多夫指出,对于基础主义的质疑并非导致不可知论,相反在基础主义中所提出的接受一个确保的理论的规则是不可靠的。在现代的理论中,必须思考一种非基础主义 的认识论方式。正如他所说的,“每一个理论家都面对着一个理论化和非理论化信仰的整体之网。并且在他的理论和他将其作为无可辩驳的认识之间,是很少产生直接的抵触。相反,最多是在他的各种信念的整体之网和他所采用的无可辩驳的认识之间所产生冲突。” 参见, Reason Within the Bounds of Religion, 43.

[49] WCB, 93.

[50] WCB, 95-97.

[51] Alvin Plantinga, God and Other Minds: A study of the Rational Justification of Belief in God. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1990), 187-211.

[52] “辩护”这个术语在归正宗认识论中的含义是,对于某人而言,一个命题P对于他确定的事物具有相对可能的程度,那么就意味着他认同对命题P进行辩护。换句话说,为一个命题得到辩护意味着为之辩护的人有论点支持这个命题。参见:WCB, 87-88.

[53] WCB,108-114.

[54] WCB, viii-ix; 2-3.

[55] WCB, 69; 167; 191-92.

[56] 这里模型的含义并不是严格的数学模型,普兰丁格认为这个模型要比数学式模型具有更多的论述文字和更放松的条件,称之为模型是因为它具有模型抽象性、概括性的特点。

[57] WCB, 173-178

[58] WCB, 179.

[59] WCB, 185.

[60] WCB, 191.

[61] WCB, 168-170.

[62] WCB, 201

[63] WCB, 214.

[64] WCB, 240-41.

[65] 同样的论证也可参见 Nicholas Wolterstorff, Divine Discourse: Philosophical Reflections on the Claim that God Speaks (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 11-16.

[66] WCB, 247-252.

[67] WCB, 252.

[68] WCB, 252-57.

[69] WCB, 258-59.

[70] WCB, 263-64.

[71] WCB, 269-282.

[72] WCB, 170。普兰丁格提供了类似威廉·詹姆斯(William James)的论证表明如果我们个人相信他人的心灵,就不能够反对相信上帝,因为这两者之间的论证结构是相似的,既不能够证明其是不合理,也不能够证明它是反理性或者是非理性的,见God and Other Minds, 187-210;

[73]在扩展的A-C模型中,基督徒相信整部圣经可以被认为是上帝给人的信息,对于基督教的信仰和实践具有权威性,但是这个信念自身并不是福音重要的核心之一,也不是基督教信念中一个绝对必要的要素,因为在基督教信念先于正典的出现。归正宗认识论持有传统基督教的圣经立场认为圣经是来自上帝的启示,从而它具有完整的权威性和真理的价值来指导信仰和道德。其次,整本圣经的首要作者是上帝(圣灵)本身。尽管圣经成书经过不同的时代和个人,但是都是圣灵的默示启示出统一的福音主题。从而就保证了通过其他不同的书卷来解释单独某一卷书卷。第三个前提原则是如果圣经的首要作者是上帝自身这就意味着经卷的人类作者所表达的含义和上帝所启示的内容之间具有多重的意义,也就是不能够假定人类作者心里所写的含义和目的就等同于上帝要启示给不同时代的人的含义是一样的,换句话,不能够认为旧约书卷的人类作者就已经明白了旧约预表新约的内容和事件。参见 WCB, 374-85; 以及Wolterstorff, Divine Discourse, 223-39.

[74] WCB, 390-91.

[75] WCB, 394-95.

[76] WCB, 374-75.

[77] WCB, 399-401.

[78] WCB, 420.

[79] 如布尔特曼(Blutmann),吉尔克(Gilkey)以及麦奎利(Macuarrie),比如麦奎利的立场就暗含着传统基督教相信神迹等信念不会为真,因为该信念为真,就会阻碍科学,因此,它是假的。

[80] WCB, 403-06.

[81] WCB, 406.

[82] WCB, 406-07.

[83] WCB, 416-420.

[84] WCB, 407

[85] WCB, 409-10.

[86] Paul Ricoeur, Essays on Biblical Interpretation. Edited by Lewis S. Mudge (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1980). Hans-Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method (Bloomsbury revelations) (London: Bloomsbury, 2013).

[87] Alvin Plantinga, “The Reformed Objection to Natural Theology.” In Proceedings of the American Catholic Philosophical Association, vol. 54, 1980: 62.